|

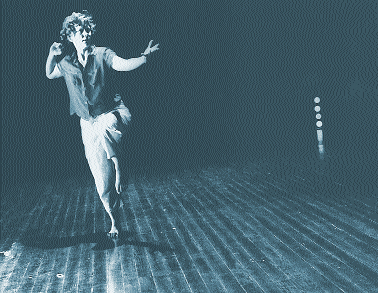

Jennifer Monson photo Heidrun Löhr |

To wit, the National Library of Australia is currently host to a travelling exhibition, Dance People Dance, curated by Dr Michelle Potter. Despite the Director-General’s comment that the exhibition “examines how theatrical dance in Australia has moved from its strongly Western European beginnings to now also reflect an ethnically diverse society”, this exhibition tells a story of Australian dance shaped entirely by its relationship to European tradition. Max Dupain’s photographs bring to life the early tours of Pavlova and the Ballet Russe which were so influential in developing our national ballet. Thrown into prominence are a group of contemporary Australian artists defined by this same theatricality: Meryl Tankard, Graeme Murphy, Stanton Welsh, Gideon Obarzanek, Paul Mercurio—all with European balletic pedigrees falling clearly on the right side of well-worn tradition.

For reasons unspecified, there are few developed references in the exhibition to other non-balletic dance traditions practiced in Australia for generations. Early Modernists are given little more than glancing recognition: the odd TasDance and One Extra poster. Neither is there material from more recent visits of, say, Steve Paxton, whose work has inspired generations of dancers in Australia. There’s an awkwardness in the way that Indigenous Australian dance is barely accommodated within the body of the exhibition.

Can interesting, successful dance be conceived of as more than commercially viable entertainment? Might different understandings of the body and dance centre on a person as an inherently mobile and expressive being? Can the body be seen as a site of inquiry, investigation and negotiation, rather than some unruly and inchoate pit of desire and impulse requiring severe discipline in order to achieve a pre-established social demeanour? Certainly these used to be fashionable ideas. The early practices of Murphy or Tankard were well-funded, ostensibly on the basis of their ‘modern’ desires. To see clearly where an artist’s aesthetic aspirations lie, you simply look to daily technical training regimes. These individuals have always sat comfortably within balletic practice. Whether they have “dented the canon” or not, to use Russell Dumas’ description of innovation in ballet, is questionable. The point is that if the idea of innovation is fashionable, its actuality is usually too problematic for public presentation.

The suggestion that our Western European theatrical heritage still provides the most influential model, would probably raise little dispute among the six member panel at the surprisingly named National Dance Critics Forum: Dance: What Next? Who Says So? Few of the panellists would have experienced dance which was about physical negotiation and investigation rather than proclamation and spectacle.

If Valerie Lawson sees the cult of the creative personality as ‘unhealthy’, to be discouraged in favour of ‘creative collaboration’, I wondered, without denigrating such enterprises, where Sydney Dance Company would be without the public charisma of Graeme Murphy. Simultaneously, even from within this ‘cultist’ mentality, contemporary economic argument requires that singular innovative artistic vision be smoothed out by less problematic, consumable, easily-toured, blander ‘international’ fare. In the case of Western European dance, you’re always in reassuringly familiar terrain, knowing how to talk, what values to acclaim. One talks about a certain style, extreme physicality and virtuosity. Dancers can travel all over the world and all partake of this same discourse. Perhaps this is what Robin Grove referred to, when discussing classical tradition in the 21st century, as “the high democracy of this art, where everyone is king”. And he wasn’t just talking about ballet, but about a classicism in which one apportions “harmonious lines in an internal coherence”, a notoriously and meticulously de- and re-constructed idea, within the post-modernist frame.

Lee Christofis, commenting on funding problems for independent artists, equated the term ‘independent’ with ‘emerging’, conveying the idea that once artists have ‘emerged’ they will no longer be ‘independent’. Further, he implied these artists might just be unwillingly ‘independent’ of funding bodies’ financial assistance. Either alternative misunderstands a more pertinent notion of independence, ie mature, wilfully artistically independent choreographic artists deliberately seeking to develop practices which speak diversely of the body—not as a well-oiled culturally ‘international’ machine, or couched in pre-defined terms which devalue difference. Such artists engage in a dialogue about practice that acknowledges Australia’s monogamous relationship with its Western European cultural referents, at the same time setting about widening cultural precepts and creating a truly independent identity.

To this end, perhaps, the antistatic festival’s centrepiece was the three ten-day workshops conducted by guests Jennifer Monson (NY), Julyen Hamilton (Spain via UK) and Gary Rowe (UK), designed to develop choreographic and improvisational practice and performance—the very practices evident in the performances which failed to impress Jill Sykes.

If a choreographer makes work to which only a specific audience can relate, is that grounds for dismissal? Such was Gary Rowe’s A Distance Between Them, in which the iconography may well have related to an audience (HIV positive men?) which did not attend. Indeed, the images remained static, distant and difficult: tight in a circular frame a woman singing Doris Day love songs, a sparse film showing a mother’s pregnant belly, a man’s throat. A tortured dancer, pinned in a hard-edged spot, dances as if forever on a steadily speeding treadmill. Tiring, repetitive phrases accumulate. Unexpectedly, sympathy finally arises for someone caught in the grip of a difficult life.

Julyen Hamilton’s 40 Monologues was like being taken for a ride. No need to specially watch for anything in this pre-edited stream-of-consciousness movement and dialogue. His art of movement non-sequitur used physical latitude that would amuse fans of old John Cleese-type word association football games. It was probably in that same wave of innovation 30 years ago that his technique developed, on the contact improvisation platform, fused in his case with more established modern techniques. These days he moves and talks with the facility and impeccable timing of a well-practiced comic.

On a similar ‘contacterly’ platform, Jennifer Monson’s work, Lure was far less straitened by early modernist vocabularies. Her strength and fluidity revealed glimpses and passages of tricky sensibility, of magical ticklishness. Sometimes the sea, its myths and enticements manifested. She stepped through waves of piquant suggestion, continuous currents of shifting sensibility. Dynamics grew and abated. She gathered her energy and hurled herself in belly flops to the floor, or else engaged with feathery and evasive wisps of tiny paper sails which rode on her breath.

New work rarely springs from nothing. Russell Dumas’ and Lucy Guerin’s works The Oaks Cafe —Traces 1 and Robbery Waitress on Bail shared a stylistic linearity given vigour and depth by webs of allusion. If, as Dumas says, ballet, like most hybrid arts, is sterile, The Oaks Cafe Project seemed to assert that the accumulated contributions of individuals (Sally Gardiner, Trevor Patrick, Pauline de Groot, Catherine Stewart), because of their particular relationships with Dumas’ artistry within their own layered experience, can suggest ways of escaping such perceived aesthetic inertia.

Lucy Guerin’s allusions perhaps highlighted an uneasy relationship between Australian/American and European escapist imagery, throwing together bland journalistic accounts of a Pulp Fiction-like restaurant theft story with the angst-ridden world-weariness of say Anne Teresa De Keersmaker’s women, who show their legs and nickers with a familiar double-edged indifference.

|

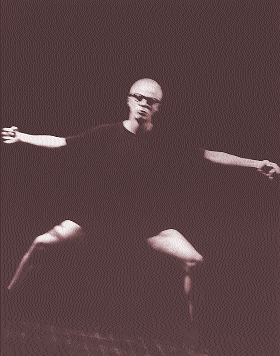

The Performance Union photo Heidrun Löhr |

Martin Hughes did not deal well with the familiar technical skills of straight contact improvisation. Helen Clarke-Lapin, his highly-skilled partner, might have taken this dance much further on her own, or with musician Ion Pierce, without losing that vital sense of physical negotiation, the raison d’être of contact, and without becoming lost in the look.

It’s a big ask of any one artist to delve into totally unknown material, as Tony Osborne may have tried to do in the velvet ca. The results, for an audience expecting refinement at least, could be construed as adventurous, if undeveloped and fairly yukky as the dancer dredged up his psychic child to play with.

A duet which did not lack refinement was Duet from Trio choreographed by Ros Warby with Helen Mountfort (cellist). Warby’s as sensitive as a delicately boned, two-footed creature can be, her movement almost disappearing in an ecstasy of sentience. In this vein too was Alice Cummins’ Lullaby, where simple, sometimes foetal movements seemed cradled in an adult text. The sound of her words soothed a difficult transition from the familiar to the unknown, like rocking soothes a baby. Six Variations on a Lie didn’t work as well in this cavernous space as it did in its more intimate home venue. There, performers formed a sparse and elegant quartet, an ensemble of soloists (dancer Rosalind Crisp, singer Nikki Heywood, sound artist Ion Pierce, and visual artist James McAllister). In The Performance Space, without the focus and cohesive physical relationships that confinement produced, the four seemed to wander alone.

|

Jon Burtt photo Heidrun Löhr |

Helen Herbertson, in a strange excerpt from her full-length Descansos, was revealed in less sympathetic light (and shadow) as a lone, almost comic figure, without the dignity and stature which characterised the original work. Shelley Lasica (Square Dance Behaviour—Part 6/version 4) spent a lot of time taping padding under her costume. If her comments referred to ‘embodiment’, or shape and line and their interpretation by an audience, the ‘deformities’ seemed to make absolutely no difference at all. A stronger statement might have been to simply leave the stage after the padding had been strapped on. No dancing at all. Leyline Co’s comment on the facade of clothing and appearance was no more compelling, despite (or because of) the high-heeled déshabille of the two dancers as they pretended to clamber unbecomingly along parallel catwalks.

During the second weekend ( March 28–29), the antistatic forums opened appropriately with Libby Dempster (“Ballet and its Other”) discussing the negative ‘otherness’ attached to non-balletic forms which, by default, are defined within the binary opposition which ballet sets up. Dance is either ballet or not ballet. Her paper was complemented by Russell Dumas’ explication of the way in which traditional European practice has defined all Australian practices in one way or another within this inescapable binary construct. With its persuasive employment of all the theatrical forms—stage design, lighting, music, set, costumes etc—it provides a kind of inscription to the mind and muscles. Unbeknownst to many practitioners, choreographic practice in Australia is situated as an art by way of its association with this inscription, the ballet trained body. So for Dumas it becomes irrelevant whether it’s deployed by MTV, musical comedy, Gideon Obarzanek, Meryl Tankard or Graeme Murphy, because what you’re seeing is a dancer trained in a regime, and the authority of this dancer’s presence is the outwardness of the display. Other traditions too, various manifestations of Expressionist angst, Butoh, ‘new’ dance practices, are paraded as innovative, but then put within this theatrical context, which simultaneously invigorates the relationship with classical tradition, while suppressing any consciousness of that relationship.

Russell Dumas outlined a different choreographic lineage: the early German Expressionist school of Laban, Wigman and Hanya Holm, having developed as an oppositional practice to European balletic tradition, escaped to 1930s America, and being full of the angst of that position, invigorated a different kind of cultural stance—one which is traceable to that country’s foundation, a rejection of these European values, and one which did not develop in opposition to the European balletic tradition. It defined itself in terms of independence, national pride, the rhetoric of which, noted Libby Dempster, Americans have felt able to work to their own ends in a variety of ways.

Dumas’ intention was not to deride Australian choreographers—despite his comment that “this is indeed the land of the dance Demidenkos”—or to persuade us to emulate the American model. Rather, he suggested that by being able to cite our cultural references, understand our historical precepts, and recognise our relationship within that tradition, we might infuse life and real innovation into an otherwise derivative national choreographic enterprise.

Dance People Dance, National Library of Australia, curator Dr. Michelle Potter; National Dance Critics Forum: Dance: What Next? Who Says So? April 26; antistatic, The Performance Space, Sydney March 21–April 4

RealTime issue #19 June-July 1997 pg. 26-27

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back