|

Baden Pailthorpe, detail: Cadence, 2013 |

All three are on show as a part of the Perth Festival. While Mori and Moffatt have solo exhibitions, unpacked from their previous lives in the US and Brisbane respectively, K’s This Lemon Tastes is part of Theatres, a spectacular installation of international artists working on video about war. Inside the cavernous Museum of Western Australia, a series of cinema-scale screens and surround-sound systems switch on and off to bring us from one warzone to another.

A second section of Theatres is at the tiny Moana Project Space, and features virtual warzones rather than actual ones. The works are set in video games, hotel rooms and the offices of Israeli architects. In Richard Mosse’s Killcam (2009), injured American veterans recuperate from losing limbs by playing video games that simulate the Iraqi war. In Eva and Franco Mattes’s Freedom (2010), Eva tells fellow players in an online first person shooter game that she is doing a performance, before being shot over and over again.

The only Australian artist in this show, alongside international stars such as Cyprien Gaillard, is Baden Pailthorpe. In his Cadence (2009) a geared-up US soldier performs a dance that bifurcates into a digital regress of his movements, so that fanning repetitions of fatigues, guns, helmets, arms and legs create a magnificent peacock-like display of military aesthetics.

|

Mariko Mori, Transcircle 1.1 (2004), Rebirth, Art Gallery of WA |

In a video advertising one of Mori’s outdoor installations, the artist’s overdubbed voice—as pacific as an automated supermarket announcement—describes the cosmic energies channelling through the cold prism of Primal Rhythm (2009), a transparent pillar of industrial scale plastic that sits in a rocky bay in Japan. In Brazil, she is planning a floating Ring that will sit atop a spectacular waterfall.

Mori’s audacious plan is to put site-specific installations on all six inhabited continents, in a conceptually rigorous reconstruction of what nature might mean to a world that threatens its very existence. She now has her sights on Western Australia, and may turn some backwater of the state into a prayer to the natural universe, and a place for destination tourism.

The contradiction and fascination of Mori’s work comes from the artificial materials she uses to provoke pagan sensibilities. As we stare at a glowing plastic simulation of a standing stone, it is difficult not to feel disconnected from the cosmos, rather than drawn to Mori’s vision of a natural universe in harmony with itself.

Mori’s video Kumano (1998) comes from a previous phase of her work, as she achieved international fame alongside the Japanese pop art movement in the 1990s. There is an intuitive sense of fun and pleasure in this early video that is lost in her subsequent work, which is at once more sincere and ambitious.

The shift from Kumano to these installations is from ludic pop to New Age, from Lando’s Cloud City to the Death Star, from pina colada to health shake. There is a corporate sheen that wasn’t there before, an impersonal program to take over the world that mobilises Mori’s charisma to further a very precise vision of nature.

|

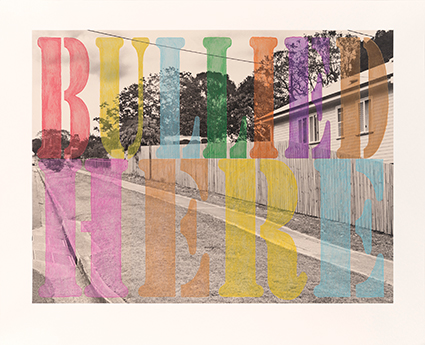

Tracey Moffatt, Bullied Here from the series ‘Spirit Landscapes’, Art Gallery of WA copyright the artist, courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney |

Moffatt is the Australian version of Cindy Sherman, as her uncanny photography taps into the suburban unconscious of Country. Her pictures of the Aboriginal settlement at Cherbourg, the Picturesque Cherbourg series, are of white picket fences and tin rooves, while the posed nudity of the As I Lie Back series resembles soft porn.

Through this exhibition it is possible to identify the genres that Moffatt returns to most persistently. These are the brightly hand-coloured photograph, childhood reflections and the sneaky camera. While montaged and stencilled photographs are part of the first genres on show here, In and Out (2013) carries on her interest in sneaky, hidden cameras, as it shows people walking in and out of a brothel doorway.

The parallels between Moffatt and Mori are strange and striking, as two successful art stars present utopian, science fictional visions laced with discomfort. The discomfort of Moffatt’s work comes from its allusions to Australian history, to families and childhoods; Mori’s from her rigorous New Ageism, her concepts of nature and peace that have been processed into industrial grade plastic.

For the philosopher Immanuel Kant, artists are not so much free as free to present the world. Art is only free insofar as it shows us how the world limits an artist’s freedom. The vision of the Iraqi artist K, walking freely in a war zone, describes his own limits living in this wrecked country. And the spectacular, consciousness-raising outdoor installations of Mori’s Primal Rhythm and Ring describe a very different kind of freedom. Moffatt, having returned from New York to live in Australia, reminds us that no matter how far away you go, you cannot escape where you come from.

2015 Perth International Arts Festival: Mariko Mori, Rebirth, Art Gallery of Western Australia, 8 Feb-29 June; Tracey Moffatt, Kaleidoscope, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 19 Feb-12 April; Theatres, Moana Project Space and Western Australian Museum, 19 Feb-8 March

RealTime issue #126 April-May 2015 pg. 44

© Darren Jorgensen; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back