|

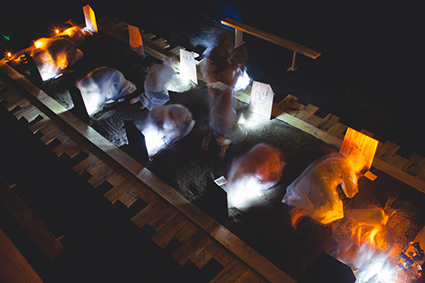

Tania El Khoury, Gardens Speak |

In our Degrees of Liveness feature you’ll find articles that reflect not only this inclusiveness and direct engagement with audiences, but also a huge diversity of topics including environmental awareness, art as labour capital, risk as art, smart phone addiction, gender fluidity and more. Live art has opened performance up to almost any subject and context—all kinds of sites and spaces, public and private. The reported performances in this edition involve walking, running (in tandem with a marathon in Finland), street protest, pole dancing and Filipino macho dancing, hysteria as performance, live dance as portraiture, fire stunt work, the animation of gallery objects, a gathering of cars and people in a raceway and an intimate work in which you read aloud personal letters involving the artist’s sex life. On a trip to the US, Caroline Wake discovers more liveness in an exhibition of digitally restored faded paintings by Mark Rothko than in retrospectives of works by Yoko Ono and Joan Jonas. There are also previews of forthcoming experimental art events: Perth’s Proximity Festival of one-on-one performances, Performance Space’s Liveworks and Near and Far, produced by Adelaide’s brand new Performance & Art Development Agency (PADA).

Helen Cole, founder and director of Bristol’s In Between Time festival of live art, who will run a masterclass for Proximity, provides a vivid account of her live art experiences. These include Gardens Speak (pictured above) by Tania El Khoury, in which the audience ‘unearths’ voices, digging deep into emotions about the war dead in Syria.

Liveness: questions

I asked people working in the arts about the current surge in liveness—live art, one-on-one performance, participatory events, real time live/digital interactivity and resurgent performance art (nowadays also delegated and mediatised). Is liveness a response to an increasing demand for authentic art-making and audience experience as an antidote to an inherent sense of isolation in the digital era? Is it a desire for both artist and audience to engage more intimately? Is it yet another drive by artists to expand their fields of practice and escape categorisation? Is liveness being rapidly commodified as another neoliberal venture with the artist as contractor? The option for respondents was to answer any of these questions or to make a statement of their own about liveness.

Theron Schmidt: it’s in the -ness

Anyone who defends the value of performance will invariably point to its ‘liveness’ as its defining, and unique, characteristic. I do it too: it’s what I tell myself makes it worthwhile to trek out on long journeys in the evening when I might rather stay home, because I want to ‘be there.’ But it seems to me what matters about ‘liveness’ is not the ‘live’ but the ‘-ness.’ The ‘live’ is everywhere, undifferentiated, all around us; only in performance do we find the ‘-ness,’ the frame around our being-together that marks it as wilful, constructed, considered. This ‘-ness’ is next to the ‘live,’ and it is the condition of being next-to, near-to, in proximity to, that gives performance its energy. This is what makes it intimate: it is an excited state, vibrating just next to the everyday, if only for a moment.

Malcolm Whittaker: from futility to joy

The turn to liveness is the latest in a rich history of futile endeavours by artists to ‘go beyond representation.’ We know it can’t be done, yet we continue the chase all the same. However unattainable such a goal might be, the effort to achieve it with ‘liveness’ is still to be applauded. An interest in liveness offers innovation within dominant aesthetics. It privileges context as much as content (often more so), and with this we have the closing of critical and authoritative distance and the opening of a space of co-habitation with the possibility of emancipation. With the rise of liveness comes a shift in how artistic virtuosity and mastery is read and understood, and work becomes charged with contemporary vitality, vulnerability and joy.

Ben Brooker: a perpetual re-thinking of the live

At a recent symposium on liveness, I was struck by how much of the discussion was shot through with 20-year-old, pre-digital age theory—Auslander, Phelan, names that have hardened into a sort of shorthand for debating the ontology of the live. Peggy Phelan herself knows the limits of the discourse she did as much as anybody to create, these days choosing to distance herself from much of her key work from the 1990s. I think there’s a clue for us here. Even as the social atomisation of the neoliberal, tech-saturated era makes us yearn for unmediated experience, the distinctive qualities of such experience seem to elude us—contestable, contingent and at the mercy of late capitalism’s co-opting, corrupting zeal. Liveness is always in retreat, and the more we attempt to bed it down, the further it seems to slip out of our grasp. This, I think, is Phelan’s frustration—that what constitutes the live must be continuously rethought as the practices of individual artists and companies are transformed in remarkable ways by new technologies, ways that fundamentally challenge traditional conceptions of liveness as the physical co-presence of audient and performer. This is a frustration for me, which is compounded by the relentless commodification of the live—but mitigated by the exhilarating new possibilities for performance that keep arising, defying easy categorisation and plugging into our deep human need to feel something.

Fiona McGregor: exploitable intimacy, commodified liveness

The surge in liveness: I think it’s good, even when it’s bad, as long as artist, audience and critical voices are heard over the din of publicity and spin.

A demand for authenticity? In affluent societies such as ours, the thirst for performance in recent years has largely been driven by saturation with material things. Performance may offer a more raw and immediate experience in its use of the body and deployment of more senses than just sight and sound as characterise two-dimensional art. This thirst is also faddish, like any other impelled by what seems to be new. Because even experience can be a commodity, and even a passing moment preserved to be re-packaged as yet another thing. Depends how it’s done, like any art.

A desire for more intimate engagement? Yes, often. But I think we need to question if we are exploiting intimacy—perhaps another longed-for state in an urban, fast-paced context. Its novelty can startle us into a sort of obeisance to the form, because intimacy—especially one-on-one—is highly codified for good reasons. It’s often taboo in certain contexts, for example staring into a stranger’s eyes isn’t something done in everyday life. I for one wouldn’t like to be eyeballed all the time! Of course this act alone will confront—does that make for a good artwork? These are questions for myself and my own work as much as for anyone else. Is that confrontation a short-cut to a state, perhaps heightened or raw, that seems therefore precious and deep, but could actually be gratuitous?

Liveness as a business? I don’t think any performance artist can run a ‘profitable business’ unless diversifying into educational, photomedia and object based work. Kaldor, Biesnbach and Obrist have turned a fat dollar with live art but they exploited much in the process—workers, bodies, public funds that could have done better elsewhere. To that extent there is safe performance art, and challenging, and the latter will always be harder to make, and harder to find.

Barbara Campbell: aliveness is the issue

Conceptually, I’m more interested in aliveness than liveness as a generative project of meaning making. Aliveness is what extends every human animal in the greater political realm. As political beings, our coming into the world is immediately registered by the state. Also on the way out. Beyond death, our having been alive is presumed to leave a legacy. During our life we’re encouraged at every turn to make our being alive count, to ourselves and others, other humans and other animals. We must prove ourselves worthy of being alive. Sometimes, proof of life is necessary. Political prisoners, the disappeared, missing persons, illegal aliens, Ariel Sharon [when in a coma. Eds], Fidel Castro, in their indeterminate states of aliveness, hold us all in suspense.

Angharad Wynne-Jones: in the petri dish of liveness

The Festival of Live Art is now affectionately known in its second iteration as FOLA, because it’s shorter, more ambiguous, and therefore better able to encompass the phenomenal breadth of liveness in the practice of live art. In FOLA 2016, Footscray Community Arts Centre and TheatreWorks will be presenting a heap of new works from across the country and around the world, many of which could be claimed by different artforms, their lineages merged, converged and reformed. At Arts House we are excited to be premiering four new works that have no performers in them…except each other as audience members and the intervention of an app or device. It seems only natural that as we create life in petri dishes so our experience of liveness is now mediated and sometimes incorporated into the digital. We only have ourselves to fear, right?

Writer and artist Theron Schmidt is Lecturer in Theatre and Performance Studies School of the Arts and Media UNSW; Malcolm Whittaker is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, researcher, performer and member of Team MESS; Ben Brooker is a freelance writer and editor who reviews performance for RealTime; Fiona McGregor is a freelance writer, novelist and performance artist; Barbara Campbell is a visual artist working principally in performance; and Angharad Wynne-Jones is Artistic Director, Arts House, Melbourne.

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. 3

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back