|

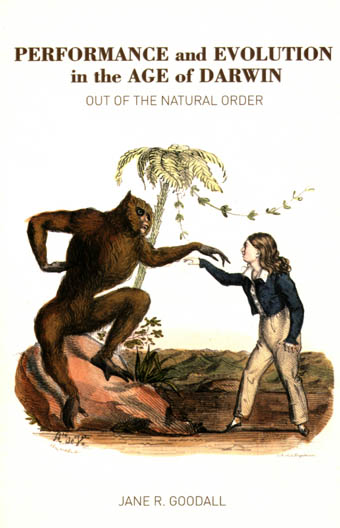

Performance and Evolution in the Age of Darwin: Out of the Natural Order |

Consider the career of P T Barnum, that “master of humbug” and proprietor of The Greatest Show on Earth who was born in 1810, the year after Darwin, and established himself as the definitive showman-capitalist of the 19th century. In his multifarious ventures, Barnum famously exploited traditions of the fairground and freak-show, assimilating all sorts of heterogenous acts and exhibits into increasingly corporatised spectacles.

In some respects Barnum resembles the great entrepreneurs like Ford and Edison, his mastery of American hype and know-how guided by an almost intuitive understanding of his epoch. Barnum’s fame and influence extended with the railroad and the printing press. As a manipulator of what we now call ‘the media’, he demonstrated prototypical canniness.

The entertainment empire Barnum unleashed was uniquely adapted to the geo-political empires of Europe and the trade routes of the United States. Goodall relates how, in his later years, nothing less than the panorama of diverse humanity became his spectacle. In 1884 he first exhibited the “Ethnological Congress of Savage and Barbarous Tribes” in which Zulu warriors, Afghans, snake charmers, “high- and low-caste Hindoos”, Aztecs and “Nautsch dancing girls” battled for attention in the show ring. Later, whirling Dervishes, Cossack riders and Aboriginal boomerang throwers (kidnapped from Queensland’s Palm Island) were added to the mix, jousting and competing in athletic displays of Olympian grandiosity that Barnum, in an awful pun, proudly promoted as the “races of the races.”

The spectacle of interracial competition and even the reference to ethnology (a synonym of sorts for ‘anthropology’) is indicative of Barnum’s attentiveness to the emerging “science of man” which, in the Victorian era, was irrevocably influenced by evolutionist assumptions. But Barnum’s engagement with science pre-dated the Ethnological Congress by decades. A defining moment occurred in 1841 when he completed negotiations to manage the ailing American Museum in New York and rapidly filled its galleries with dwarfs, flea circuses and anything else that was “monstrous, scaley [sic], strange or queer.”

To “startle the naturalists and wake up the whole scientific world” was one of Barnum’s professed ambitions. With a dry restraint that allows her wonderfully rich material to convey its generous endowment of humour, Goodall describes Barnum’s purchase of the “Feejee Mermaid”, a zoological assemblage, that in 1825 had been profitably exhibited at London’s Bartholomew Fair and even then dismissed by scientists as a hoax.

Barnum’s introduction of this rather shopsoiled fraud to the American market indicates his genius for publicity. The event was pre-empted by a cunning press release that hinted at the mermaid’s scientific credentials, verified by a “London naturalist”, one Dr Griffin, who had conveniently arrived for an American tour. Dr Griffin was Barnum’s stooge Levi Lyman, who had cultivated the role of expert scientist in various ruses. When the mermaid toured the US in 1843, a South Carolina naturalist called the bluff in a newspaper article, describing how the mermaid was constructed. Characteristically, Barnum managed to turn even this setback to advantage, recalling the exhibit to New York, playing up the “scientific controversy”, and inviting the public to come and judge it for themselves.

Goodall shows how Barnum monitored and exploited developments in evolutionary theory. The American publication of The Origin of Species in 1860 precipitated the revival of an exhibit titled “Barnum’s Incredible What is It?”, a creature purportedly captured in Gambia and promoted as Darwin’s missing link. This might be seen as straightforward repackaging of older traditions of the freak show and carnival, but Goodall points out that the primal fascination of such human or quasi-human ‘monstrosities’ was never the exclusive domain of the showground. Naturalists had long been interested in ‘curiosities’ and peculiar ‘productions of nature.’ Theories of evolution put the spotlight on freakishness and grotesquery, bringing new attention to phenomena that had long been the bread and butter of carnival and showmanship.

Not only Darwin but also his predecessors like Saint-Hilaire and Lamarck (both evolutionary theorists) had brought special attention to natural variety, arguing for a vision of nature in which forms were not fixed but subject to constant mutation and transformation over time. Royal Academicians certainly sneered at vulgar spectacles like freak shows, and would have applauded the 1840 legislation that outlawed theatrical entertainment at Bartholomew Fair—a pivotal event in the modernisation of London which suppressed ribald and supposedly subversive performances: traditions that dated from medieval times.

But science was imbued with its own codes of display and showmanship. Surgeons practise in theatres because an audience of students or colleagues was once de rigeur for an operation. Some appeal to theatricality was essential if the budding scientific institutions were to attract the masses, let alone be pedagogically effective. Museums provided talks and entertainment to spice up otherwise lifeless exhibits, while zoological gardens never entirely shook off their relationship with the circus—nor could they afford to if they were to maintain the flow of paying customers.

While much in this book is side-splittingly funny, Goodall’s ambition is serious. She contests a monocular view of the 19th century that developed in the 20th, a position in which, “...evolutionary theory came to mean Darwinian theory. It no longer encompassed a range of competing analyses and interpretations, and was accorded monolithic status as one of the great paradigm shifts of modern intellectual history.”

Goodall’s astonishingly agile tour through music halls, opera houses, theatres and circuses is an admirable demonstration of the remarkably heterogenous ways in which performers and audiences dealt with the new ideas about themselves that evolution threw up: the connection with apes, the loss of certainty about the human form, the terrifying prospect that primeval forces might lie secreted in the ‘modern man.’

Dracula and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde are literary works that explore and exploit these anxieties. Dracula’s creator, Bram Stoker, was the manager of the acclaimed “beast actor” Henry Irving whose arresting movement from the “diabolical to the divine” (Auerbach) inspired the blood-sucking aristocrat—“a stalking category crisis” as Goodall calls him.

All this substantiates her contention that a history of performance provides a paradigmatic understanding to the culture of evolution. No other form is so intricately concerned with the fullness of corporeal possibility. Curtailed by bodily limits, yet seeking constantly to extend and redefine them, the floating qualities of the ballet dancer or the versatility of the ‘protean’ mimic who could embody a member of any class, race or creed and then dissolve like magic into someone else, encapsulate not only the hopes but the culture of anxiety that accompanied all this conjecture about what people are and what they might yet become.

This is a book that covers considerable ground in little more than 200 pages: a history of performance which, in the tradition of Richard Sennett and Greg Dening, pans the stage, the audience, and the forces that combine to give them a dazzling frisson. Although I enjoyed the gallop, there were times when I wished for more. Perhaps it will come in future books.

Jane R. Goodall, Performance and Evolution in the Age of Darwin: Out of the Natural Order, Routledge, London & New York, 2002, ISBN 0 415 24378 5

Jane Goodall is Research Director at the College of Arts, Education and Social Sciences at the University of Western Sydney.

Martin Thomas is ARC Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Technology, Sydney and author of The Artificial Horizon to be published by Melbourne University Press in October.

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 6

© Martin Thomas; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back