|

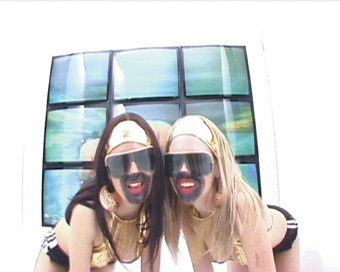

The Kingpins, Versus, 2002 Courtesy the artists |

The first instalment of Video Hits took place in the central gallery with large rear projection screens, headphones strung from specially constructed overhead beams, velvet-covered bean bags and the high-concept works of music video stars Michel Gondry, Chris Cunningham and Spike Jonze. The second part of the exhibition consists of many smaller screens with headphones lining the length of one wall. The vision has broadened to include more Australian works and an historical survey featuring a range of music clip makers. There are also several key works of video art that engage with music and the visual representations of the music video form. Some of these confront the clichés of music video production with parody, others with creative re-imaginings. All engage in a conversation about the intersection between music, art and the moving image, encompassing the substantial divide between the television format of music video programming and the gallery setting of video art. It is this juxtaposition that generates the exciting frisson of the exhibition, facilitating new connections across genres of video practice and reconsidering the relations between differing histories and conventions.

The selection focuses on parallels and crossovers between contemporary art and music video production with a number of clips by major art-world figures. These include Wolfgang Tillmans’ clip for the Pet Shop Boys’ song Home and Dry and Doug Aitken’s for Fat Boy Slim’s Rockafeller Skank. Damien Hirst’s Country House clip for Blur highlights how dated both Britpop and Young British Art are in 2004, while one of the oldest clips in the display, Derek Jarman’s The Queen is Dead (1986) for The Smiths, holds its own admirably with skilful montage and chroma-key effects deployed to explore some of the aesthetic dimensions of iconographic Britannia.

Literally alongside the high-concept clips of auteur music video creators Gondry and Cunningham, made for big-name music stars such as Bjork and Kylie Minogue, is a selection of video artworks with different aesthetic and ideological prerogatives. Much contemporary video art continues to articulate themes first explored in the feminist video work of the 1970s. Personal subject matter encompassing identity, autobiography and remembrance, relation of self to others and exploration of self through personae was frequently expressed in the 70s via the direct address of the solo artist, whose body often formed the centre of the work. This same spirit of enquiry is still very much in evidence in today’s video art, with the added patina of ultra-voguish low-fi 80s fetishism.

Video Hits includes key works by Pipilotti Rist and Annika Strom. Strom sings her own compositions to the accompaniment of a simple Casiotone, and a meandering personal video featuring her parents, daily chores, footage filmed from a television screen and a diary of her art practice. Rist is shown singing along to other songs, overpowering and distorting the original with her version. Katie Rule’s garage re-enactment of the dance sequence from Thriller also affirms the body as an expressive site. While some may agree with Rosalind Krauss’ tart characterisation of video art as fundamentally narcissistic, a simplistic dismissal of these works as self-indulgent play-acting necessarily ignores their power.

These works continue the feminist project of validating personal history as subject matter and its challenge to dry formalism and ossified notions of ‘the beautiful.’ These artists conflate or sublate the division between art and life and understand art as a social practice. As part of this ongoing use of video art to generate discourse about ‘the personal’ and its political dimensions, artists featured in Video Hits can be seen to be reclaiming the female form—not just from male artists, but also from the commodifying proclivities of the video clip genre, where extreme examples of exploitation and unhealthy representations of women are, disappointingly, iconographic staples.

In addition to these performative urges are video artworks which emphasise editing as the central expressive device for moving images, such as Art Jones’ juxtapositions of popular songs with obscure and disturbing imagery, or Ugo Rondinone’s hypnotic re-edit of a Fassbinder film with different music. Though still crucial, music operates here as a creative element of post-production, rather than the raison d’etre for production.

Video art, while it emerged from the technology of television, is often centrally concerned with distancing itself from that medium, and its preoccupation with disavowing its ‘frightful parent’ can be seen at Video Hits in works such as the clips by Sydney video artists the Kingpins, which parody the unoriginal and aesthetically obnoxious visual clichés of many rap and metal clips, and Tony Cokes’ text-based dissertations on the politics of the music industry.

The exhibition has not tried to conflate video art practice with music video production; rather, it situates the 2 as overlapping in many areas (Jonze’s infamous Praise You street-theatre clip is also a masterful piece of video art), but with different prerogatives. In video art, ‘representation’ is unmoored from the band/performer as a central structuring element and floats freely through critique, parody and creative probing, whereas art and technique in video clips, ultimately, are subordinate to selling the band and their music. The music video genre doubtless offers a platform for remarkable innovation and the Video Hits selection showcases this with some stunning commercial works, particularly those from Gondry. However, the clever curation of video artworks that not only engage with the music video form, but mount a critique of music television, means that Video Hits also constructs a kind of intra-medium discussion.

In the same way that video artists work with existing imagery or songs and rework them, much of Video Hits is about recontextualising the art of music clips in the environment of the art gallery, where they can be considered alongside reflexive video art. Given the increasing attention being devoted to the music video form as art, it’s a timely vision and a bold project exploring the multifaceted bases of video practice.

Queensland Art Gallery, Video Hits, various artists, Stage 1 Feb 21-April 12, Stage 2 March 27-June 14

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 40

© Danni Zuvela; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back