|

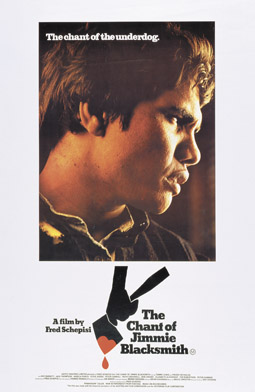

original poster for The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith |

Above all, Reynolds sees The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith as an emblematically 1970s film, its makers motivated to create for Australian Aboriginals an icon, possibly a black equivalent to Ned Kelly. However, the nature of the Governor/Blacksmith crime, the axe murder of a group of white women, undercuts any sense of heroism. More problematically, the murders might well have been triggered by the racist and social indignities heaped on the Blacksmith brothers, but their impulse in book and film comes from a deep-seated savagery, a return to a primal condition. I recall teaching the novel and seeing the film at the time of its release and being disturbed by this very factor. I was not surprised at the film’s poor reception, despite some public debate about wary audiences being in a state of racist denial. As Reynolds points out, the film’s violence, reinforced by the bloodied axe which was its promotional icon, confirmed it as a film of its time, working the sex and violence theme but here in a racial context. Reynolds sees Keneally and Schepisi, like the 19th century journalists before them, as racialising the violence (as an atavistic urge), when it was more likely to have been motivated by class tension, in a man who didn’t see himself as Aboriginal.

Of course, it was a bold move by Keneally and Schepisi to attempt to engender empathy for the plight of Aboriginal people by using such a challenging story, with its excesses of provocation and response. But what Reynolds reveals, in a few pages, is the very different circumstances of Governor’s life from the film’s identification of Blacksmith as a conventional Aboriginal of the time. True to the period of the second half of the 19th century, Governor was typical of many Aboriginal men of mixed descent who assimilated to varying degrees with white society, went to school, were literate in English, had jobs or made careers for themselves and did not necessarily identify with fellow Aboriginals (nor is there evidence of Governor’s being ritually initiated as Blacksmith is in the film). Of course, all of this was to change with the introduction of the Aboriginal Protection Board in New South Wales in 1883 (removing mixed descent children from their families), the growth of forced segregation and the establishment of reserves and, in 1901, “in the new federal government...Aborigines were denied the right to vote in federal elections.” A few pertinent, educated observations aside, there is little sense in the film of Blacksmith as a man of this period.

The film’s account of Blacksmith’s post-murder bushranging (contentiously signalled as a ‘war’ on white society) is largely diverted into moral point making in an encounter with a white liberal. It pales next to Governor’s three months as an bushranger. He was an effective strategist—there were many robberies—and he was brutal—four killings, a number of woundings and a rape. Fear of his gang was widespread and a huge operation was mounted to capture him. Had the filmmakers wanted a more heroic, if still deeply problematic Blacksmith, they might have attended more closely to Governor’s history. After his capture in the film, Reynolds reminds us, a speechless Blacksmith declines into torpor (recalling a line in the novel: “a fatalism native to his blood”). Governor, however, was renownedly garrulous, “with a cocky sense of achievement, of becoming a celebrity”, and spoke keenly to journalists and his captors of his achievements. Governor, and Blacksmith, had been shot in the mouth during the capture. In the film this prevents Blacksmith from speaking. Reynolds suspects, as he tracks the loss of voice for the Aboriginals in the latter part of the film, “It’s as though Keneally and Schepisi didn’t want him to talk. It’s their story—not his.”

Reynolds also finds the values of the film confusing. If a primal urge is first seen as being at the root of the murders then the second half of the film shifts towards a suggestion that Jimmie’s problem lies in miscegenation, that he is caught between primitive life (initiation, his full-blood brother Mort) and Christian culture, but is forever at the bidding of his Aboriginality. Reynolds sees this in the contrastive skin casting of the performers, in makeup and hairstyling, in Mort’s stereotypical ‘bush native’, Jimmie’s breaking into “an apparently ‘instinctive’ tribal dance” and “[w]hen on the run, Jimmie’s initial improbable ignorance of tribal law is gradually overcome as an inherent Aboriginality breaks through...” As with the opening shot of the film, Jimmie’s intiation, so it ends, after Blacksmith’s off screen hanging, with a shot of cockatoos rising in flight—”conventional romantic pantheism”, writes Reynolds, and a further muddying of psychological and cultural cause and effect.

Reynolds asks if it’s possible to make an Aboriginal legend out of an obscure historical figure, a complex, possibly psychopathic one with white ambitions and no sense of being a warrior on behalf of his people. (As Reynolds notes, Schepisi is happy to “interpret violence as war” without “allowing Blacksmith to explain what his political objectives were.” Instead, Blacksmith howls “War” into an oddly reverberant landscape.) Reynolds suggests that if Schepisi wanted a hero, and one reasonably well known he could have looked to Jundamara of the Kimberley region and his Bunaba resistance from the same period (his life was recently dramatised by Perth’s Black Swan Theatre Company with Bunaba Films, RT84, p34 ).

Reynolds takes particular exception to the film’s cinematography, not in terms of its skill or effectiveness, but in the inspiration taken by the cinematographer Ian Baker and director Schepisi from Tom Roberts and the Heidelberg School: “…we are faced here with two quite different and competing traditions with the dialogue aspring to contemporary relevance while the cinematography looks back to the aesthetic ideals of the early 20th century”, ideals freed of Aboriginal connection to the land.

The book ends by addressing the big picture: the effect on the industry of the film’s poor reception and its place in our cultural history. Schepisi lost a quarter of a million dollars on the film and has said he “felt very guilty about its effect on the Australian film industry.” Reynolds thinks, given the filmmakers’ noble intentions, it was ironical that “the commercial failure of Schepisi’s film made it very difficult to make further films about racial issues for 10 or 20 years. It became the conventional wisdom of the film industry that films about Aborigines, and especially about racial conflict, woud never be commercially successful.” It was a long path to The Tracker, One Night the Moon, Beneath Clouds and Rabbit Proof Fence—all released in 2002, two of them by Aboriginal filmmakers.

As for the film’s standing as a work of art, Reynolds declares it “an unsatisfactory hybrid.” He says of the novel what is true of the film, “[it] takes a real historical character but invents so much that the story loses its touch with past reality. It is neither one thing or the other.” As a cultural artefact, Reynolds feels that “we learn more of the filmmaker and the writer than we do about Jimmy Governor and his brother. What we see is the way in which progressive, liberal white Australia sought to come to new understandings of the nation’s history while still encumbered by remants of discredited racial thought.”

Above all Reynold says the film tells us more about the 1970s than the 19th century. For that reason and “[de]spite the commercial failure of the film, Schepisi created scenes and images which are unforgettable and which will remain as important contributions to the intellectual and cultural history of Australia in the second half of the 20th century.” This comes somewhat as a surprise after Reynolds’ thorough and eloquently argued challenges to almost every aspect of the film. But perhaps it’s the kind of thing you’d expect of an historian, for whom the film is a fascinating document of our recent past, of issues and events which still haunt us and inhibit the well-being of Aboriginal people. Now a generation of Indigenous filmmakers are in the process of making their own feature films. What history will they tell us, and what history will they make? Reynolds’ book is another fine addition to Currency Press’ Australian Screen Classics series.

Henry Reynolds, Australian Screen Classics, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, series editor Jane Mills, National Film & Sound Archive, Currency Press, 2008

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 24

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back