|

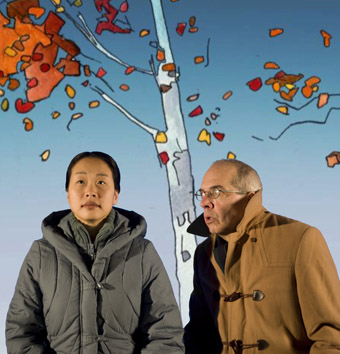

Sherry J Yoon, James Fagan Tait, My Dad, My Dog, Boca del Lupo |

This whimsical passage comes early in Boca del Lupo’s My Dad, My Dog, a delightful show that plays live action against a vast canvas of animations that are a wonder to behold. The dog scene offers us one possible way of exploring what’s to come. While taking in the whole, we might use a selective eye to pick out details that suit our sense of narrative. A similar technique is used a little further along. James Fagan Tait (there are no character names in the program) is an ornithologist searching for the rare white-necked red-crowned crane, which is found only in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) that separates North and South Korea. He stands before the screen, now filled from top to bottom with animator Jay White’s depiction (a fluttering watercolour) of the DMZ. Looking not-too-hopeful about ever finding the rare bird, Tait exits. A live-camera feed from a mini-stage set up at the left side of the stage allows White to project his own hand holding a magnifying lens onto the large screen. It finds the crane in the foliated background. So this story is also about not seeing things — like seeing the tree shake but missing the crash. Framing certain things implies excluding others.

And there’s another story-telling technique at play here. Telling a story is always an act of translation. There’s a possible source event, someone puts that event through a subjective filter and transmits it to someone else. The storyteller may use the biological machinery of his or her body (lungs, larynx, mouth etc), or technological aids — a pen, a camera, a computer. I think we usually picture story telling proceeding in that order: original event, internal translation, re-telling. But in My Dad, My Dog the order is reversed. Sherry J. Yoon imagines her way back to a North Korea she has never visited and to a woman who doesn’t exist but is a plausible type for a relative she might have there. It’s like creating a photo album of a vacation you never had.

Well that’s just what fiction is, you say. And you’d be right. But Yoon takes pains to frame this fiction as a search for a missing part of her family story. She offers biographical details of her ‘real’ life (“I am Korean”) as the starting point for an investigation into her relationship with her father. She imagines her father reincarnated as a North Korean dog. When Yoon is not performing herself she plays the part of her North Korean alter ego, who works for the government monitoring and limiting the movement of visitors to her country. She visits the dog chained up in an alley and talks to it, believing it will understand her (in one hilarious scene the dog complains to a fellow canine that he can’t understand the woman because she’s speaking English). Yoon, as herself, returns to the stage periodically to tell us which parts of the story are true (and exactly what she means by ‘true’) and which are inventions. The difference is as important as we want to make it.

Often the characterizations are made deliberately flat, while animations like the dad-dog almost jump off the screen and display a psychological complexity the humans lack. The blurring of fact and fiction is kept in play. We realize that, to some extent, we all assemble our ‘selves’ from a patchwork of memories, dreams and desires. We put a frame around that which we accept as ‘I’, as ‘me’, and leave out the rest.

The autumn colours on screen and the delicate figures of Alicia Hansen’s piano compositions give the show a very west-side-of-Vancouver feel. There’s a lot of light-hearted dialogue about the character of the city: “Vancouver seems liberal but it’s conservative. But not as conservative as Toronto.” These comments aren’t serious digs. For the most part, My Dad, My Dog doesn’t try to be the last word on any issue. But after a while it starts circling itself. The content and episodic structure gets repetitive —I don’t think this is a deliberate narrative strategy. The animated sequences, mesmerizing as they are, become devices not always integral to the theme. The attempted resolution — “sometimes there are no answers” — felt pat to me. It felt too much like an answer, it created closure to that which might have remained open.

But then again, maybe I was looking in the wrong direction. It would be like me to put a frame around the thing everyone else thought was irrelevant. You know, looking at the tree and missing the crash. Oh, but maybe that was the point. Or lack of a point. Um, throw up another cool animation, the critic is leaving the stage.

Boca del Lupo, My Dad, My Dog, created by Sherry J Yoon, Jay White, director Jay Dodge, performers Billy Marchenski, James Fagan Tait, Sherry J Yoon, animation and scenography Jay White, music Alicia Hansen, costumes Reva Quem, lighting Jeff Harrison, Jay Dodge; Roundhouse Community Arts and Recreation Centre, Vancouver, Jan 25-26, Jane 29-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 - Feb 3

Alex Lazaridis Ferguson is a theatre artist based in Vancouver. He writes plays, acts, and occasionally directs. He's also a founding member of the performing poetry ensembles, AWOL Love-Vibe and VERBOMOTORHEAD. His writings on theatre have appeared in publications such as Canadian Theatre Review, The Boards, Transmissions.

© Alex Ferguson; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back