|

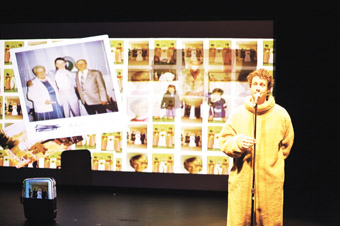

James Long, Clark and I Somewhere in Connecticut photo Shannon Mendes |

The faces in the photographs projected constantly onto screens beside or behind the bunny-suited narrator (in part James Long as himself) are blurred because he is legally restricted from revealing the identities of the family. Without seeing these strangers’ eyes, it’s hard to connect. However, the impact of the visual images is gradually displaced by the power of a few key anecdotes that are told several times, each time with subtle alterations. And, because names can’t be used, the narrator gives each person a voice-gesture nickname, such as grandpa Superman (swoops arms to one side, kicks foot up behind) or Sad Green (strokes L-shaped hand along cheek) or “Sschcrrh” (swings fists briefly beside hips)—“whose name is not fun to say.” A lighthearted dance, in a way, gradually underlies the storytelling and is partly what leads us from image to word.

Family photographs are intimate in some ways and illusory in others. The narrator—simultaneously Long and a fictional character—is somewhat lonely, wishing to join his lawyer friend and his family on their trip to Disneyland, or pretending to be the person in an album who has a job as a bunny actor for children’s events. He sometimes uses the photos to put himself to sleep, he says, imagining happy events at the family’s summer cabin; later, he meets the widow and learns those were weekends where the disintegrated family put up with each other for a few painful hours.

The narrator also loves dogs. He was walking his dog in a heavy rain when he found the suitcase full of photos, and he treasures the fifth album because it’s devoted to a toy pomeranian named Mandy. But even that love may be a fiction. One of the repeated anecdotes is about a kid working at a kennel who feels for a sickly, runt puppy abandoned by its mother and drowning in its phlegm. The kid decides to kill it by throwing the poor thing against the building. The owner of this story isn’t clear—the narrator tells it first, but eventually three others tell it with varying detail on video—but all like to agree that the puppy’s last thought was probably “wheee!” The way this anecdote morphs through repetition, and the way it’s impossible to know who “owns” the story, embodies the issues of ownership connected to the photo albums.

Clark and I Somewhere in Connecticut tells an entire family history through photographs. But what sticks is the visceral image (spoken not shown) of a Japanese man cannibalizing a young woman (the other most repeated, and true, anecdote) and the quadrupled experience of hearing how the puppy dies. It’s a fascinating reversal of how we usually give our eyes top authority when it comes to looking at pictures. If we’re willing to make that shift, maybe we’re also willing to consider whether story ownership is determined by who cares about it most—who digests it, who makes it theirs emotionally and physically. Or maybe we’re not willing, because we feel protective of our photo albums. Either way, the layered storytelling co-created by Long, onstage video artist and co-performer Cande Andrade and six offstage members of Rumble Productions is superb. The bunny suit always carries a sheen of sadness, and the nice-guy narrator—willing to help an old lady on a bus—is someone we trust. The unusual disempowerment of the photographs creates an open channel for us to linger in the narrator’s emotional world, and he tells us about it so well.

Rumble Productions & Theatre Replacement, Clark and I Somewhere in Connecticut, created by James Long, Cande Andrade, Owen Belton, Camille Gingras, Craig Hall, Anita Rochon, Jonathan Ryder, Maiko Bae Yamamoto; Performance Works, Vancouver, Jan 30-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 - Feb 3

Meg Walker is a nomadic fiction and non-fiction writer currently based in Vancouver, where she also spends plenty of time making visual art.

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 4

© Meg Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back